Magical Medieval Poitiers

A lady saint, a queen, a martyr, dragons, and sacred Romanesque beauty

Hey Epic Human,

First I want to present my offer! Both companies that offer psychometrically validated assessments say they will be raising their prices next year, so my cost will likewise increase.

This is a golden opportunity (many people can’t believe I’m offering it at nearly cost!), so jump on it now before their prices go up. (Hint: it might make a lovely Christmas gift for someone.)

After my last newsletter’s lovely lull, our pace accelerated enormously! You wouldn’t believe all that’s happened over the past couple of weeks. I teed up nearly 100 photos to share, but I daresay that’s a tad too many—so I shall précis as I can. Suffice it to say my photo timeline is cluttered with Romanesque sculptures, churches, medieval buildings, and joy.

Just for laughs, we’ll start with a glimpse of Lady Liberty:

Hundreds of “Liberty” statues are scattered around the world (8 of them standing in Paris), and this Liberty Enlightening the World is the centerpiece of a small park in Poitiers, where we had a sightseeing extravaganza.

Poitiers is historically famous for the epic Battle of Poitiers, a significant conflict during the Hundred Years’ War, which took place on September 19, 1356. Fought between the English under Edward the Black Prince, and the French under King John II, this battle was a major English victory and marked a turning point in that war.

Due to the number of churches in this area, Poitiers is known as la ville aux cent clochers (the town of a hundred steeples)—so several churches were listed on our day’s agenda.

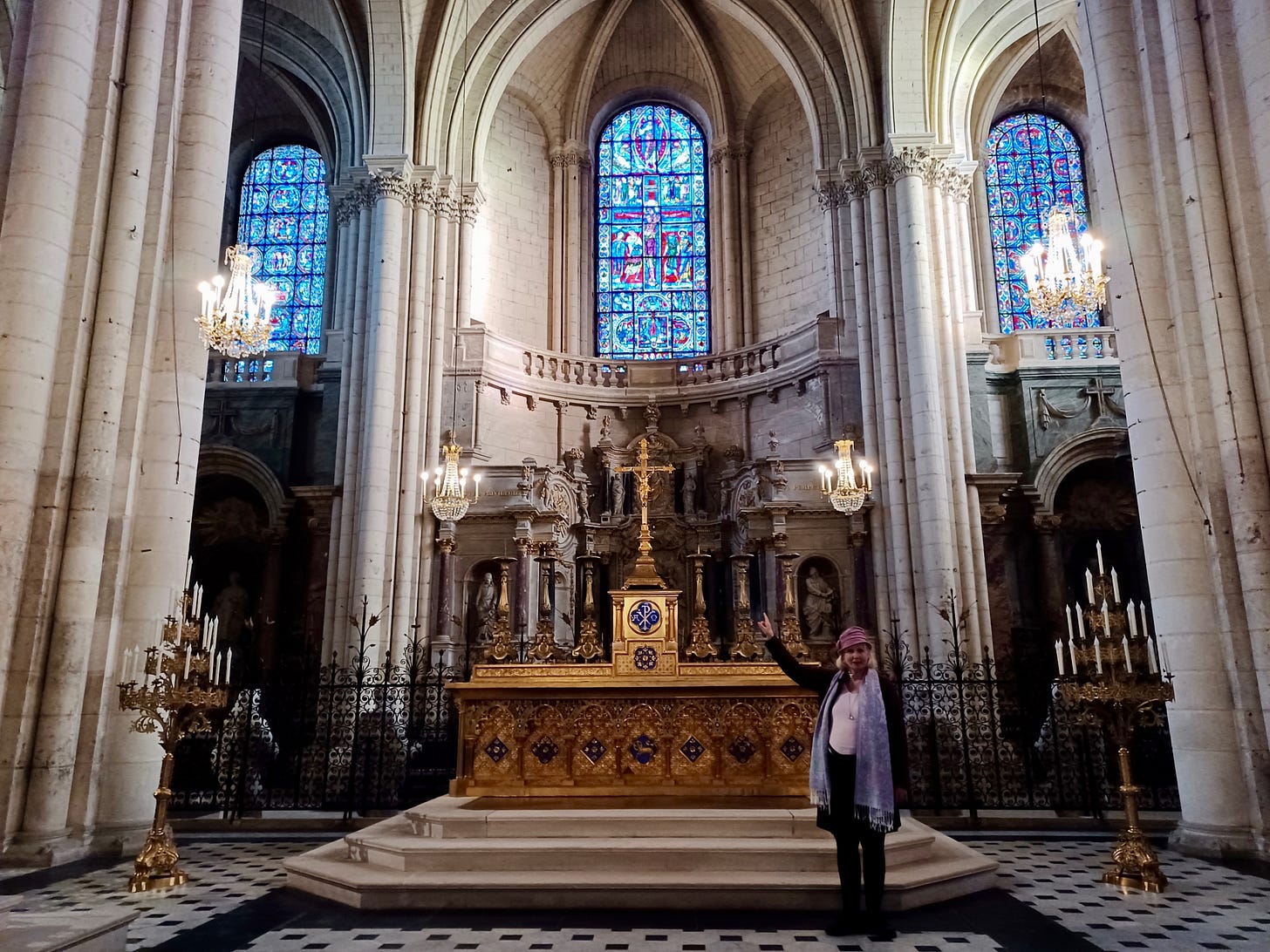

First we returned to the extraordinary Cathédrale Saint-Pierre de Poitiers, said to be the oldest Romanesque church in France—where they booted us out last time. I wanted another chance to view the stained glass in broad daylight since it dates from the 12th and 13th centuries.

This end window, known as the “Crucifixion Window,” contains figures of Henry II and Eleanor and was completed around 1165, making it one of the earliest stained glass cathedral windows in all of France, and is thought by many to be the finest single work of stained glass in the world.

Almost everything about this church, rumored to have supernatural powers, remains unknown. One tale takes place in 1202, when Poitiers was under siege. A traitorous employee of the town hall promised to deliver the keys of the city to the enemy for a large sum of money. But on Easter Eve, when he entered the mayor’s office, the keys had vanished! They were found the next morning... lying in the hands of the statue of the Blessed Virgin. That same night, the Virgin Mary, Saint Hilary, and Saint Radegonde appeared to the enemy soldiers and bade them to flee.

This miraculous episode and divine intervention are said to have saved the city! This was also the cathedral where Eleanor was crowned Duchess of Aquitaine alongside her husband, Louis VII, who was crowned Duke of Aquitaine. When her marriage to Louis VII was annulled and she married Henry II of England, the cathedral played host once again, so it has impressive royal connections.

From here we walked a few yards across the street and visited Musée Sainte-Croix (the Holy Cross Museum). Not only did we get free admission unexpectedly, but I daresay it was one of the best museum experiences I’ve ever had. It’s like they knew my tastes!

This museum houses rich archeological collections dating from prehistory, to the neolithic era, then the Roman period, and after that, the early Christian period. When upstairs, we entered the Middle Ages galleries, and eventually passed through their fine arts department dating from the 14th century into the Renaissance, and then into the beginning of the 20th century.

The neolithic section was fascinating, since human figures are carved on several stones (lots of pregnant women and/or prominent vulvas), but they were lying flat in a case and impossible to photograph due to light reflecting off the protective glass, so you’ll have to take my word for it.

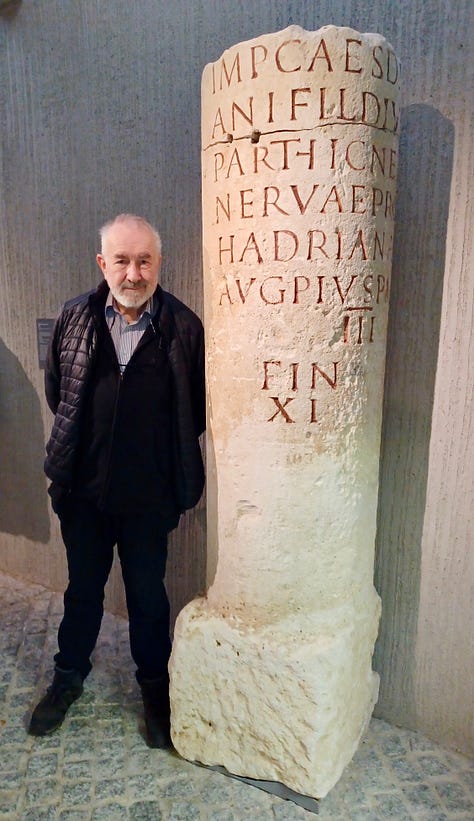

From there we moved into the Roman section and then into the early Christian era.

Robin is a big fan of the Romans and this link to Hadrian is a throwback to our time in Athens and our visits to Hadrian’s Wall. The marble statue is thought to be the Roman version of a Greek Athena, daughter of Zeus, with a Gorgoneion (Gorgon’s head) emblazoned on her breast, dating from the 1st century. One of the major divinities in antiquity, Athena appears here as the goddess of wisdom and art, and the nice museum guard offered to take our picture with her.

The female pair is meant as an image of bounty, and the oversized hands on Daniel with the lions on the end of a late 5th century sarcophagus fascinate me. The naif style of art on those early Christian plaques is charming, and the representation of Rafael (Raphael) and the other figures amuse me.

Those final two figures represent the penitent thief and the impenitent thief who were crucified alongside Christ. This 7th–8th century bas-relief is thought to be one of the Western world’s oldest representations of the crucifixion of Christ between two thieves, and it came from a Merovingian Christian underground tomb that’s now embedded in the cellar of this museum.

From downstairs we moved upwards into the Romanesque period (swoon!).

Of course the capitals are the most overtly Romanesque with their quaint, funny figures. I love the elephants most—apparently carved by someone who has never seen an elephant. The Christ figure is classic Romanesque style, as is the arch composed of griffins, accompanied by an extremely weird deer (carved that way, or weathered into that appearance? Hmm…). I also love the orant figure—an “orant” is a representation of a figure, typically female, with outstretched arms and palms up in a gesture of prayer often shown in ancient and early Christian art.

One capital took my fancy, which is titled “La Dispute” or “The Argument,” dating from the late 11th or early 12th century, and is classified as a masterpiece of Romano-French art. It’s one of the museum’s great treasures.

It presents a scene of argument followed by reconciliation. On the right side a man is pruning the tree he’s standing in, which may be the matter in dispute. On the main side (shown above), two men grasp each other by the beard with one hand and brandish serrated axes in their other. On either side of them, two women attempt to hold them back. On the third side, two men with wooden legs (the combatants?) are reconciling.

This work is believed to have made society more peaceful by protecting the weak and supervising the use of weapons.

I shot a brief (:33 second) video of it so you can view all three sides and fully appreciate the piece:

This scene could have been inspired by some fable from poetic literature, but the iconography ultimately condemns violence.

From this part of the museum, we moved into later works:

The image on the left shows the remains of a painted keystone once mounted over the entrance to a local convent. Carved sometime between 1490 and 1510 it shows how brightly colored these sculptures were at that time, and not the bleached remains we typically see now. The 15th century wood carving on the right shows my old friend Saint Jacques of Compostela standing atop the head of a demon.

At this point in our visit we took an intermission and made our way to a nearby building that is open only during limited hours: the Baptistère Saint-Jean. This small, unimposing building is the oldest surviving church in France. It was built atop Roman foundations from a hundred years previous (in the 4th century) and then reconstructed in the 7th century to what is seen today.

It is the oldest preserved Christian monument in all of Europe—the oldest existing Christian building in the West—and it features Romanesque and Gothic wall paintings from the 11th–13th centuries.

The baptistry holds a museum containing Merovingian sarcophagus covers and even includes a Carolingian altar table, which is seen in the apse.

Its most unusual feature is its baptism pool—yes, I said pool. Originally part of the original Roman fountain, it is octagonal in shape, and was used until around the 8th century. People would be completely immersed in the pool during baptism rather than bending over a font to have water poured over their heads. (The gated surround railings were added once it became a museum.)

This building has undergone many good and bad phases over the years, from its intended use as a center for full immersion baptisms, to severe neglect during the occupation of the Visigoths in the 5th century, through its religious heyday in the late Middle Ages, to its sale for use as a warehouse after the French Revolution, and on into the 20th century when its true historical importance was finally recognized. It is a prominent example of Merovingian architecture.

Although it has undergone partial demolition, several additions, and numerous rebuilding efforts over the years, when one steps inside, it still retains the feel of its Roman origins.

This ancient ceiling fresco with its Christ medallion looks down upon the altar in the apse.

After gawking at this marvel both inside and out, we headed back to the museum and picked up where we left off…

Robin was greatly taken by this recently restored 16th–17th-century Dutch painting, The Feast of Balthazar. It depicts the biblical episode recounted in the book of Daniel when King Balthazar invites dignitaries from his kingdom to a feast during which he desecrates sacred vessels stolen from the Temple of Jerusalem. During the festivities, a hand mysteriously appears and draws signs on the wall. Only young Daniel, a Hebrew in exile, knows how to translate the three-word message: Mané, Thécel, Pharez, meaning “Counted,” “Weighed,” “Divided.” It meant the king’s days were numbered; his soul was weighed and found too light; and his kingdom will soon be divided. That same night Balthazar dies and his rivals take over his territory.

The painting is luminous! It looked like something you’d find at Disneyland—it was positively spooky how it caught our eyes.

I lingered over sculptures by Auguste Rodin’s famous mistress, Camille Claudel. This museum has an exceptional collection of ten of her sculptures, three of them acquired in 2017.

This is the third largest public collection of works by Claudel in the world and the second largest in France (and just my luck many of them were away on loan—ironically to the Chicago Art Museum OR the Getty Museum in Los Angeles).

This next piece might have been my favorite piece in the museum—although it’s soo hard to choose one!

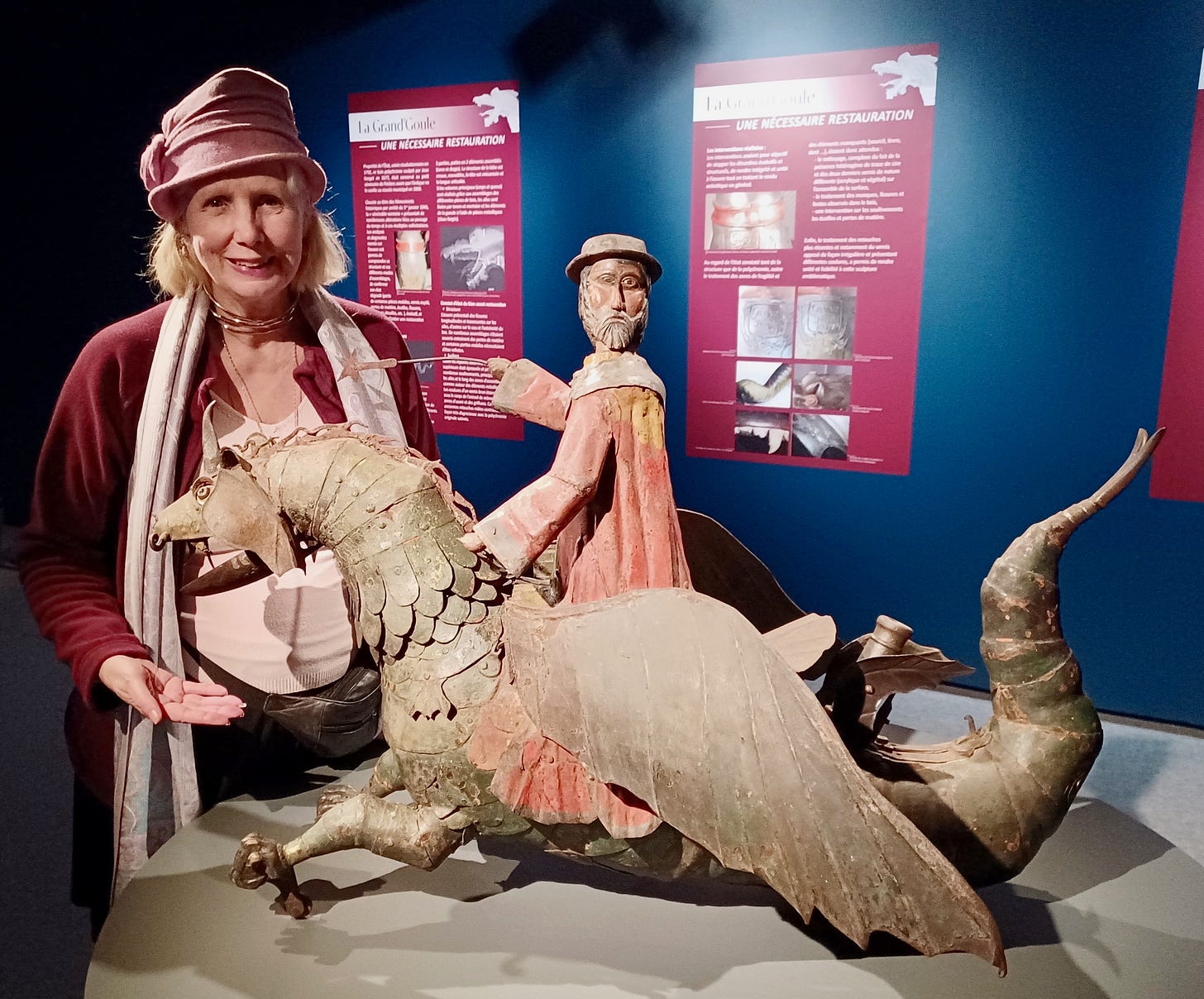

This particular piece is titled Dragon and Rider, but appears to be undated. It was donated by a collector. It is referred to as an “automaton” or “mechanical toy,” with plates, pulleys, strings, and rods, allowing them to move and many parts of it are articulated for movement and effects.

The Grand’Goule (corrupted from grande gueule, “great gullet” or more simply “big mouth” or “big maw”) is one of many French dragons. This particular dragon terrorized Poitiers until it was slain.

One legend claims Saint Radégonde killed it with a fervent prayer—a prayer which literally flew like a projectile and hit the dragon like a crossbow bolt. (More about her shortly.)

Traditionally, a Grand’Goule effigy was brought out on rogation days and paraded along with a relic of the True Cross. At those times it was referred to affectionately as the bonne Sainte Vermine, the “Good Holy Vermin.” It would be decorated with ribbons and banderoles and treated with respect. As it passed, cherries, tarts, and dry cakes called “snout breakers” were tossed into its mouth as people shouted, “Good holy vermin, pray for us,” and “protect us for the year to come.” The beast thus transformed into a protective figure.

Three days following our museum visit we returned to Poitiers to take in more sights; specifically, the churches we missed. First up was Église Sainte-Radegonde, a medieval Roman Catholic church dating from the 6th century that takes its name from the Frankish queen and nun Radegund (Latin Radegundis; also spelled Rhadegund, Radegonde, Radegunda, or Radigund), who founded the first monastery for women in the Frankish empire in the year 552. Most importantly, she is patron saint of Poitiers.

So who was Radegund? She was a formidable woman by all accounts, but it’s hard to separate fact from legend (especially considering all of the “begats” that must be sifted through). In a nutshell, she was a Frankish Queen who escaped a brutal royal marriage and found refuge in the church.

Founding the first abbey for women in 552, she dedicated her life to helping the poor and needy. During her lifetime, Radegund was known as a healer, and her medieval cult became associated specifically with her power to heal gout and ailments of the limbs. Radegund reportedly performed many miracles, and, in 569, after sending some hand-sewn cloth to the Byzantine Emperor, Justinian, she received, in return, a piece of the Holy Cross, a relic still kept in the abbey she founded.

This church was destroyed and rebuilt multiple times, so remnants from across the centuries may be found in its architecture.

Radegund died in 587 and was buried in this church she’d built, which was promptly renamed after her in her honor.

Many pilgrims traveled to visit the church from around the world in order to pay homage to Radegund. In 1012 her remains were exhumed by order of Abbess Béliarde for public veneration, and the entire church was rebuilt after a major fire in 1083.

Radegund’s remains were kept in the church crypt below the raised choir (as shown above) and it was an important destination for pilgrims to visit and pay their respects to her, a practice that continues to the present day.

In the second half of the 13th century, miraculous healings of many pilgrims who visited the church are documented, especially in the 1260s.

The tomb was desecrated in 1562 during the Wars of Religion. When Poitiers was sacked by Protestant troops, remains of the saint were reportedly burnt and scattered, although some charred female bones and ashes that could be those of the saint were rescued and later collected into a lead casket that was placed into the sepulcher that is seen today. Near the tomb is a white marble statue of Radegund (seen above).

Until after World War I, Sainte Radegund in Poitiers was the great pilgrimage church of the region and it is colorful, striking, beautiful, and enchanting.

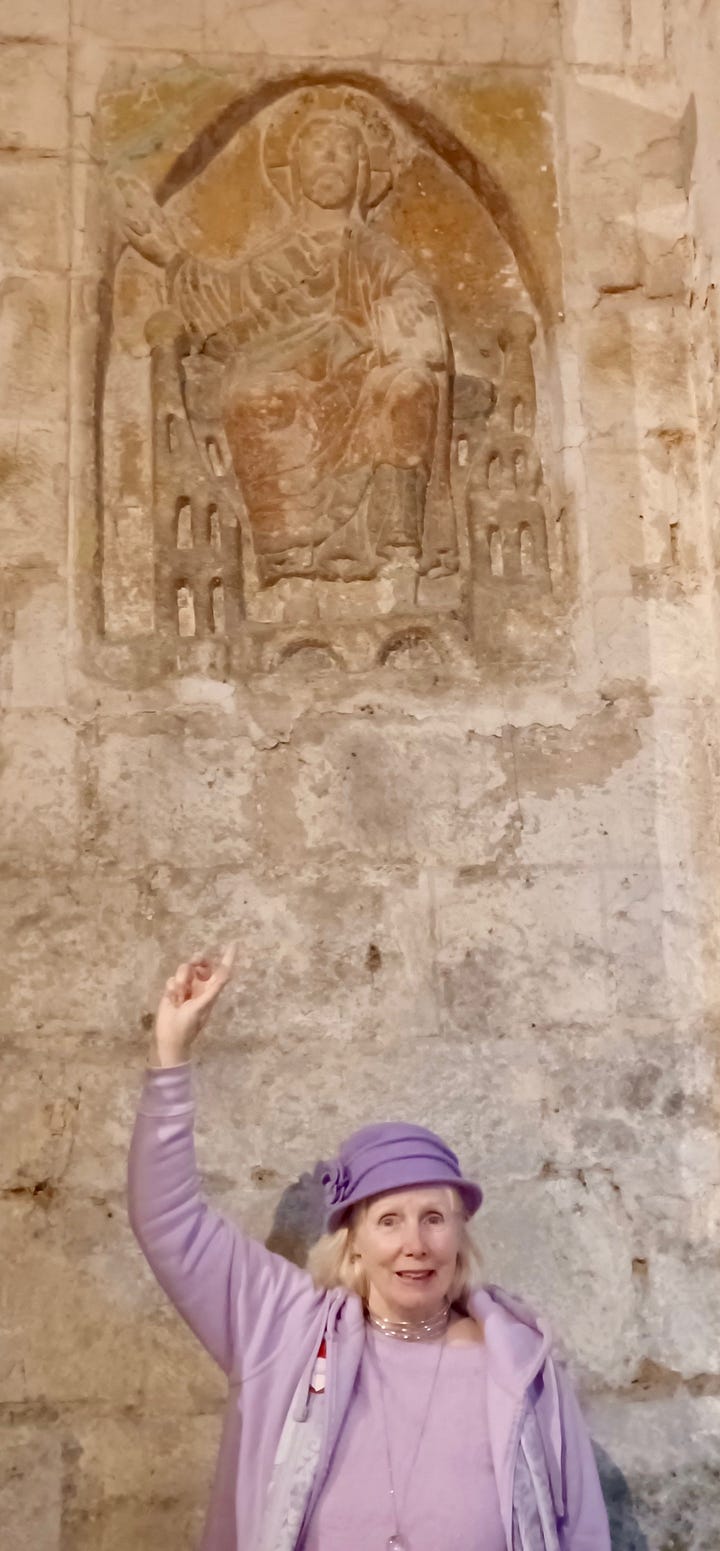

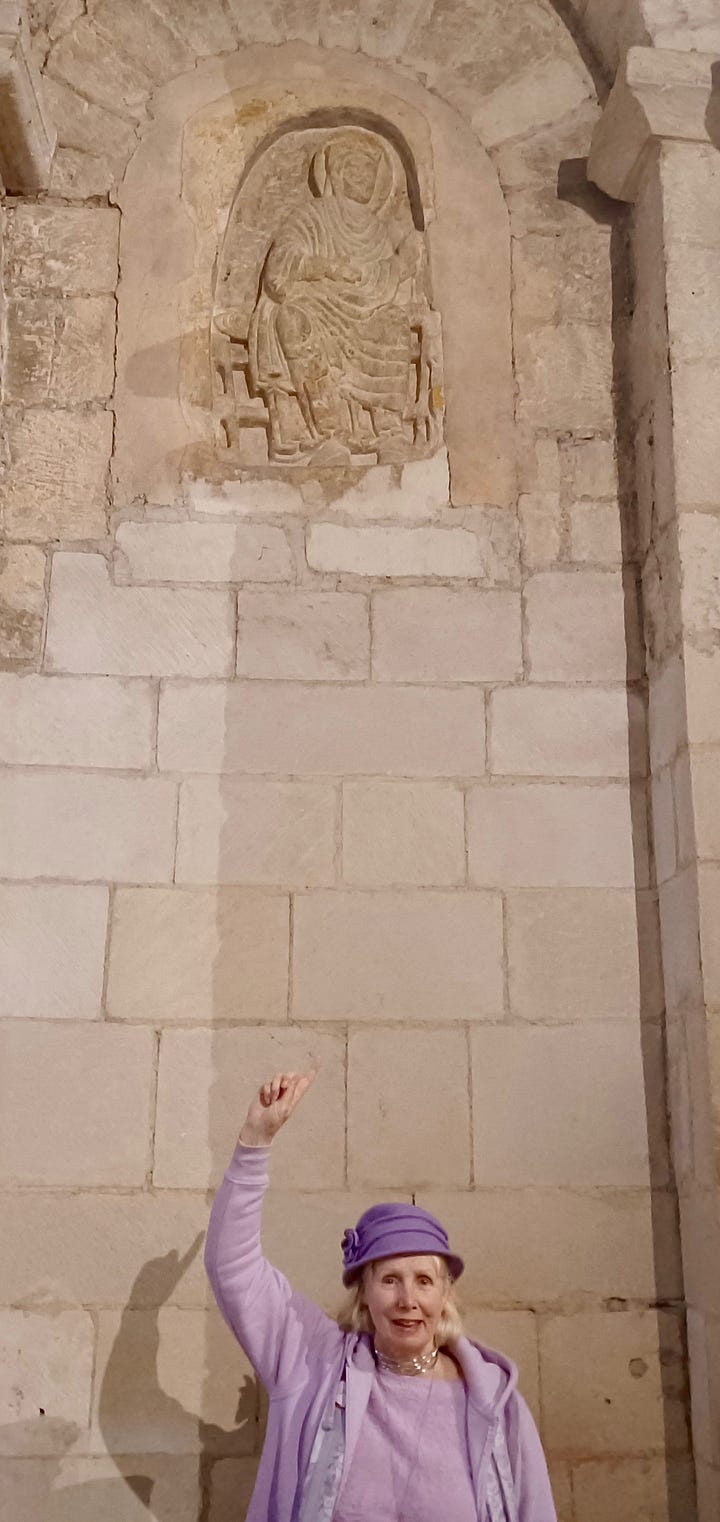

In the bell-tower porch, two reliefs face each other that were re-used from the old Romanesque facade. One relief represents Christ in Majesty and the other shows a seated woman who could represent Saint Radegund or the Virgin Mary—or even a personification of the Church. The two reliefs are likely the remains of a single sculpted ensemble, and traces of polychromy color are still visible.

The lower image is a mosaic on the floor in front of the choir, and the other shows the exterior of the church, with its beautifully curved Romanesque lines.

As we were departing the church, this 16th-century flamboyant Gothic gate caught our interest, along with the ancient stone wall on the side.

We also came across these half-timbered houses that appear in many French villages. Many are beautifully preserved and lend an authentic medieval tone to the surrounding area.

We made our way to the Palace of the Dukes of Aquitaine, known formally as the Palais de Justice. Unfortunately, that venue is closed for renovation and off limits to our sightseeing eyes. Below is an image found on the internet that shows what it looked like before all the scaffolding was put up—but we couldn’t get near its perimeter.

This medieval palace was a fortress, surrounded by now-vanished watery moats that separated it from the rest of the city. So many things happened here during Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine’s lifetime—from the time she spent with Louis VII and her wedding night with Henry II to witnessing royal council meetings with people like Thomas Beckett.

Eleanor reconstructed the Great Hall of the Palace beginning in 1192. This Hall of Justice, or “Hall of Lost Footsteps” (where a footfall was silenced by the vastness of that space), or even “Hall of Lost Causes” was the only part we could visit, and it was delightful to imagine Queen Eleanor entertaining her retainers and visiting nobility here in her final years.

This was the largest room in all of Europe at 164 x 56 feet. Eleanor wanted somewhere to host grand events and showcase her power as both Queen of England and Duchess of Aquitaine. After years of being undermined by her two royal husbands, this was her domain, and she filled it with troubadours, dancing, and fun. A place of glittering celebrations, it became known as “the courts of love.”

After the English burnt much of the Palace in 1346, parts were rebuilt in the 14th century, including the addition of a grand fireplace at the end of the Great Hall.

This image I found online gives some sense of its size.

Joan d’Arc was interrogated in this room in 1429, which then led to this site appearing in Luc Besson’s 1999 film on Joan: The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc.

Our next visit was to the Église Notre-Dame la Grande, whose west front is recognized as a masterpiece of Romanesque religious art. It truly was breathtaking.

People flock to its façade simply to stand and gaze at the statuary with awe. Even the locals can’t help but be mesmerized. It’s like a storybook made of stone with all of its sculptures and statues. As Dennis Aubrey wrote:

The penalties of a life of sin on this earth were displayed across the entire west façade. The judgment of God, the long lines of saints, and the roiling and writhing agony of the sinners were expressed in lasting stone to remind us of the rewards and penalties that await each of us at Judgment. Demons fed souls through the very maws of hell; the Devil cheated during the weighing of souls, even trying to capture a marginal soul by cheating lest he lose one more to Paradise.

In this universe, it was not enough to barely get by; one had to believe wholly and completely, and the way to believe was writ large on this great building for all to see. There was never an excuse for ignorance. Guidance was available to all. Free will dictated the path taken by each soul and the judgment of God accepted no excuses.

Inside were many elaborately painted surfaces.

This brightly colored medallion on the ceiling in the rear is quite magical.

Running out of time, we bounced through these hallowed halls rather quickly. And from here we rushed off to the church of St-Hilaire-le-Grand, built in the 11th century over a Roman graveyard and dedicated to St. Hilary, the first bishop of Poitiers (a man!).

Hilary was born into a pagan family in Poitiers and then converted to Christianity after reading the Scriptures. He was appointed bishop here in 350 AD, after which he took up a defense of orthodox Christianity against Arianism, which held that Jesus Christ was only a man, not God-made-into-man.

Thanks to the tomb of St. Hilary, this church attracted many pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela, and it has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998. The fate of Hilary’s relics is not known for certain, but one account says they were destroyed by Protestants in 1572.

If you are perceptive, you will notice something unusual about our view of this venue:

That’s right: it’s DARK. We could not get here before the light faded, and I could see little more than shadows on the exterior.

Worse, there was no light switch to be found on the inside, and other than St. Hilary’s shrine (seen in the lit arch directly behind my head), the little I could see was with the help of a tiny flashlight.

Apparently this is what it looks like during daylight hours (image found on the internet):

This church was originally covered entirely with Romanesque wall paintings representing bishops of Poitiers in the nave; one of the earliest images of the apocalypse in the choir (said to still be there); and drawings in the side chapels around the ambulatory. Someday I’d like to see it with the lights on, sigh.

There was so much more to Poitiers, most notably some additional sites honoring Joan d’Arc and some details I missed as we rushed through (sigh). But it was a rewarding visit, and it certainly scratched my itch for the Romanesque—and who knows? We may land a sit nearby in the future so I can pick up what I missed this time around.

In my next post I’ll describe another trip we made to some Romanesque sites before starting our big exit move out of France towards the UK and our imminent Christmas celebration.

Until then, have a Happy Holidays!

warmly,

-Dr. Vicky Jo